Perspectives in Place What Black Matriarch Artists from Ohio Taught Me About Safety

Written by Amanda D. King - 4 min read

Toni Morrison and Ming Smith remind us that Black spaces are not merely places we occupy; they are sacred, self-sustaining sites of belonging, grounded in solidarity and the pursuit of safety central to liberation. I first encountered their works in high school, a time when I was navigating girlhood in a predominantly white school. Accessible but not inclusive, this environment was not designed with my protection in mind. Through their stories and images, I discovered alternative sanctuaries – places where Blackness, in all its complexity and beauty, was held.

In my creative practice, which strives to cultivate spaces that affirm and center justice, the works of Morrison and Smith have been instrumental in challenging the false narrative that people must endure inhospitable environments to gain power and access – an idea commonly mistaken for safety.

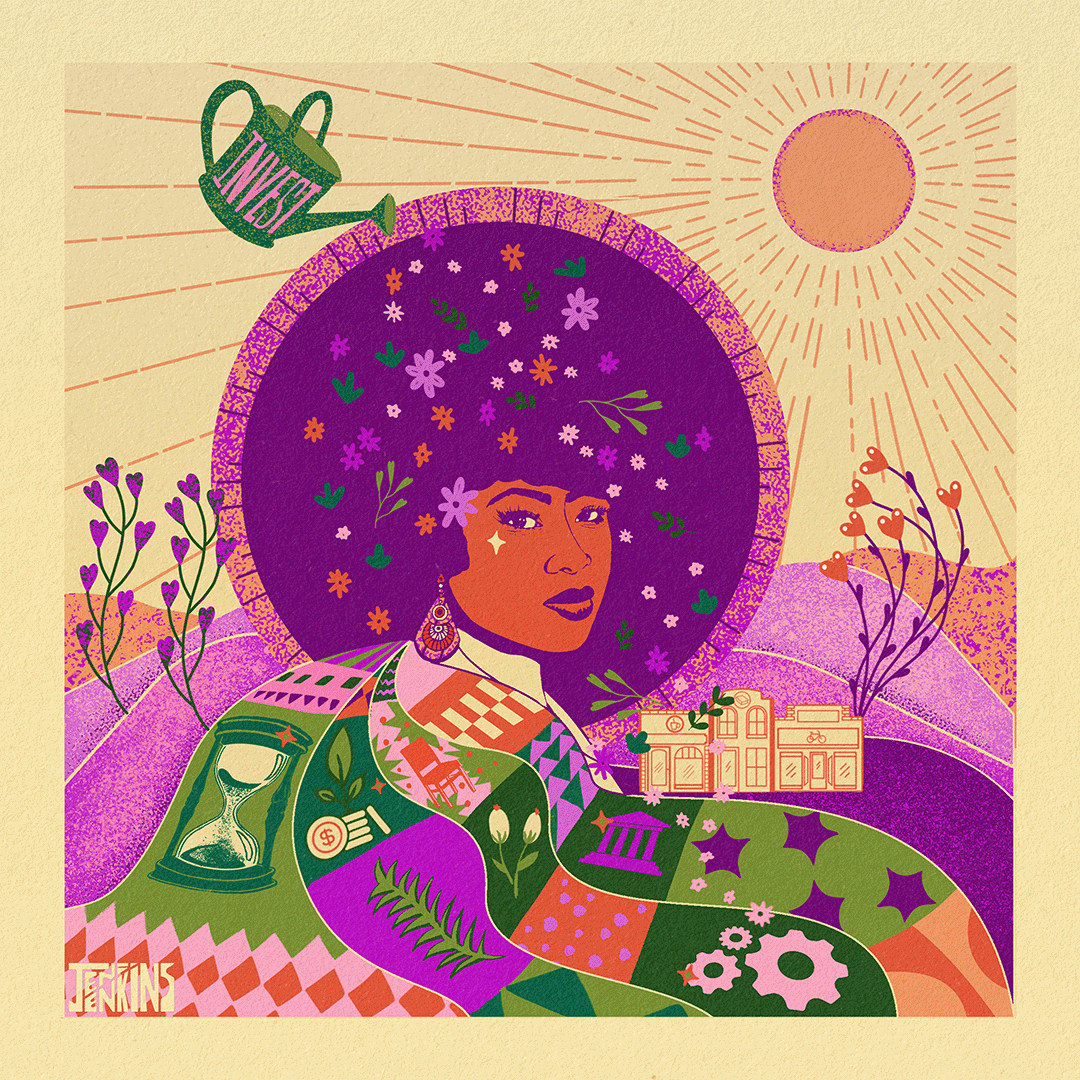

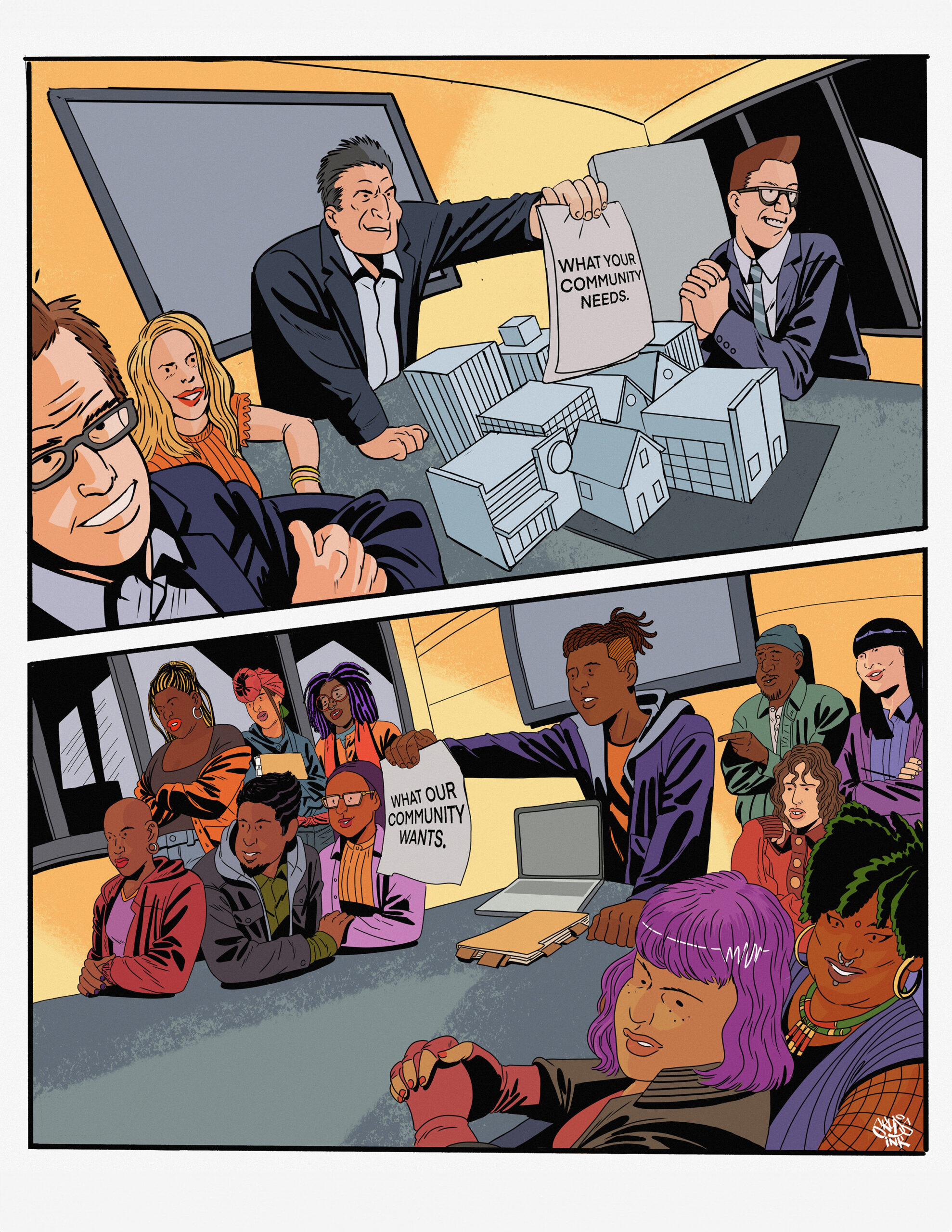

In The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison introduces Pecola Breedlove, a young Black girl who believes that possessing blonde hair and blue eyes will shield her from the cruelty around her. In her search for acceptance, she loses her sense of self and spirals into madness. To remind her of her beauty, her friends plant marigolds, but the flowers fail to bloom, unable to grow in the infertile soil. Pecola’s story serves as both a commentary on Black girlhood and a critique of the structural inequities that undermine Black communities. Morrison writes, “When the land kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim had no right to live. We are wrong, of course.” This passage, particularly the latter part, has shaped much of my cultural production, including The Marigolds, a public art installation I mounted in Cleveland’s Buckeye neighborhood. The installation depicted a multigenerational Black family who, in the face of gentrification and cycles of disinvestment, hold space for their neighbors to thrive. These families, like the marigolds, exist in a constantly shifting environment – built up and torn down, too volatile for some to grow – but they persist, cultivating alternatives for survival.

In spaces that demand conformity, what is offered in the name of safety is often rigid and oppressive. The openness within Black communities and the networks of care we’ve built offer a model of true safety. These are spaces where people are nurtured, where collective efforts lay the foundation for solidarity and a shared future. Just as marigolds grow in fragile environments, Black communities, when cared for, also flourish.

Ming Smith’s Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere is a meditation on openness in Black communities. While shot in Pittsburgh, Smith’s eye transcends a specific place, instead focusing on the relational experience of Blackness and its multilayered dimensions. By employing long-exposure photography, her technical openness allows light and movement to permeate the frame. In doing so, Smith redefines the boundaries of the photograph and the contours of Black existence as infinite. In her work, safety is not an elusive concept; instead, it is omnipresent, fluid, and deeply embedded within a communal ethic of inclusion.

Within the liminal space between visibility and invisibility, the subject in Smith’s work moves through a landscape that is both familiar and unknown. To an untrained eye, the shadowy figure – at one with the surroundings – may provoke unease. But when viewed through the lens of openness, Smith’s work offers quiet assurance, a reminder that safety and wholeness can be found in environments designed to nurture and hold us. Her work challenges the idealization of safety, instead grounding itself in the complex realities of survival.

Both Morrison and Smith situate safety in everyday life, portraying it as a dynamic process deeply connected to mystical elements like dreams, ancestral wisdom, and intuition. These unseen forces sustain Black communities as living entities, capable of transcendence.

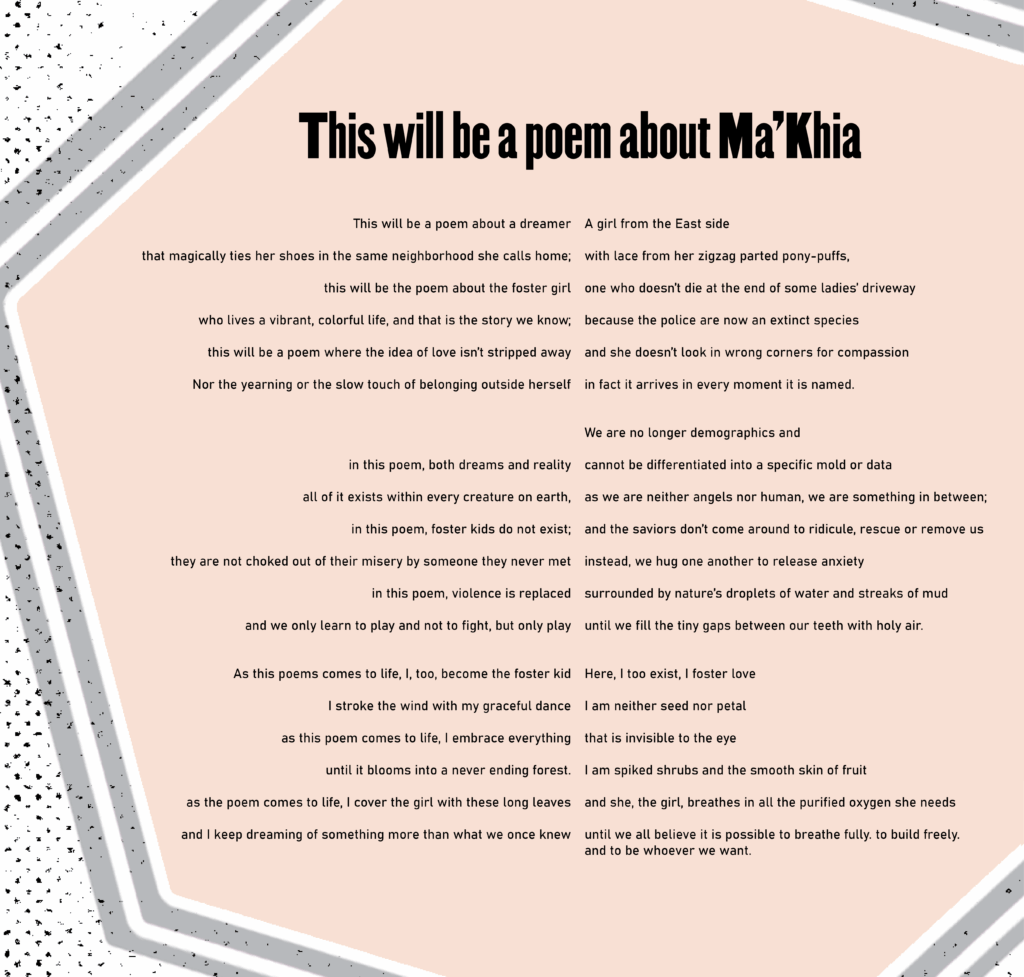

Safety in Black communities is delicate, perpetually at risk from the roots of systemic injustices. Yet, this fragility does not undermine our inherent right to protection, nor does it diminish the creativity we bring to its pursuit. In our openness and solidarity, we are rooted. Even in the face of forces that seek to dismantle us, we find the courage to envision and build spaces where we are not only safe but free.

Amanda D. King is a visual artist, cultural strategist, and social justice advocate. Her multidisciplinary practice spans photography, design, and social practice. Through her work, she explores grace, converging notions of beauty, identity, and spirituality into both visual language and social action. King is also the co-founding creative director of Shooting Without Bullets, a nonprofit creative agency that promotes justice and equity. The organization models an alternative arts ecosystem designed to address, refuse, and eliminate inequities in both the arts and society.