There's No Place Like Home

IN(TER)VIEW, Johan Matthews - 11 mins read

We caught up with Johan Matthews to talk about the significance of homegrown institutions in community development work … and the narratives that hold them back.

What brought you to community development work? What keeps you motivated to keep doing it?

Johan: I came into this work because I wanted my children to grow up in a better world.

I was born and raised in Kingstown on an island nation now referred to as St. Vincent and the Grenadines. There, in the postcolonial context of my homeland, I was a naive native, shielded from the Black-White notions of racism that we find ourselves preoccupied with in the U.S.A.

I came to the United States with my family in 2005. Even back then, I recognized that, as an immigrant, my family took an incredible leap of faith; that they left everything behind for the promise for a brighter future for their children. This path required assimilation, so I put on my blinders and marched onward. Gradually, though, as I progressed in my own life, I began to realize that there were invisible forces at work, negatively influencing the lives of people who looked like me and my own identity began to shift.

In fact, I became Black.

Eventually, my journey of self-discovery and the identity shifts I experienced therein – from Indigenous to immigrant to Black – brought me to the realization that my identity had been shaped by invisible forces without my consent or consideration, the impact of which disconnected me from my cultural inheritance as a member of the African Diaspora. Ultimately, it gave rise to a deep desire to guide my people toward our righteous collective destiny.

When you think about the role of community development in supporting people’s self-discovery and collective destiny, what are the implications for the kinds of institutions we need to build?

Johan: One of the first things I noticed as I began to live in the diverse, urban communities of the United States was that the landlord, teacher, policeman, doctor, loan officer, and politician are all different from you, especially if you’re identified as Black. In these communities, the physical and social infrastructure are maladapted instruments of Eurocentricity and white hegemony. Unsurprisingly, this disconnection, which is by design, precedes vast, racially defined inequities in housing, education, criminality, health, economics, and politics.

Creating institutions that are controlled by members of the community they are intended to serve is a promising path out of this inequity. Unfortunately, that is not the goal of this system. Consequently, community development, as it is largely practiced today, will never lead to any real or lasting change.

Homegrown institutions represent an opportunity to create social infrastructure that emerges out of and is responsive to a community’s essential qualities and needs. They are spaces that not only reduce the harms caused by the disconnected systems that litter our communities, they allow us to create value that can be sustained intergenerationally. They reinforce the idea that you belong in your community.

What are the barriers that keep homegrown institutions serving communities of color from starting … or from thriving when they are started?

Johan: I would say the first is a cultural barrier of miseducation, formally implemented through the school system but also informally through media and the specific roles we see ourselves cast in.

This miseducation has misshapen our identity and diminished our sense of self. For example, if you were miseducated to think that all you are is a descendant of slaves, as opposed to the descendants of Kings and Queens, you’re going to now pick up the tools of education or finance and use them in vastly different ways. One will use them to escape their circumstances and live like there is no tomorrow, the other will use them to build a kingdom. In community development, it’s common practice to describe beneficiaries as helpless victims in need of intervention. This too miseducates us about what is possible.

The second barrier is the disconnection that miseducation facilitates.

If you’re born into a community where you don’t see anyone like you holding any positions of power and it’s been that way for generations, you’re likely to become disconnected from those institutions as well as from the possible roles that you could play in your own community.

That disconnection also breeds doubt in the people who aren’t from your community but do hold institutional power, like the loan officer whose limited personal experience prior to his role leads him to believe that Black people aren’t equipped to organize thriving businesses. He prejudges. That racial prejudice inclines him to ask a bit more questions of a Black applicant than others, causing less Black applicants to make it through to an approval. This act of racial discrimination may be repeated dozens of times in interactions between that institution and individual applicants of color. When this dynamic continues to play out within the finance industry in a particular community, we see racial inequity – disproportionately less thriving Black businesses than others. That inequity is what the next generation of aspiring business owners and loan officers enter into, and it reinforces the story that the loan officer had in the first place, that Black people aren’t equipped to run a thriving business, and the self-fulfilling cycle is reinforced, from prejudice to prophecy.

The third and most insurmountable barrier is that outside communities benefit from the status quo.

In schools, for example, we can imagine a kind-hearted teacher, who commutes an hour every day to teach a class in a diverse, urban school. She is unable to relate to her students, but there’s a teacher shortage, and she needs the job. Unfortunately, she has a difficult time with the class and ends up kicking an energetic Black boy out of the classroom. The school recommends that he take medication, but his mother declines. Her husband, a police officer, who also commutes an hour to work in this community, ends up locking that boy up because now he’s in the streets instead of at school. That boy is then sent to a juvenile facility located in the teacher’s community, where two of her cousins serve as prison guards. Once the boy is released, his parole officer recommends he be sent back to jail for failing a drug test, so he loses his job working for her brother-in-law, who owns a local fast food franchise.

When we consider this story in the context of the often expressed data point that the boy, a Black male, is at least three times more likely to get kicked out of class, put in jail, and once released, return to jail, we can recognize that this system impacts these two communities in diametrically opposed ways: one represents a thriving livelihood; the other, perpetual poverty.

That really resounds with dominant community development narratives we’re uncovering around perceived risk, perceived lack of capabilities, and blaming individuals instead of systems. Another that comes to mind is the Blank Slate narrative, where the sector is willing to resource outsiders to come into communities of color and test their ideas, without any real engagement or resident leadership.

Johan: Unfortunately, there’s an inclination in our communities to accept any improvement as progress.

If a community of color experiences a homelessness crisis, for example, then when local funds are made available for outside investors to build an affordable housing complex, people tend to see it as progress because there’s likely been no improvement in the situation for some time. Thus, it seems like every investment is an impact investment, even though no wealth or lasting change is being created in that community. In many of these projects, residents neither benefit from the income, nor experience the sense of pride in doing the work. Often, the community doesn’t control, or even provide input, over what work is done. Both the community members and the municipality may perceive a good investment and a problem solved, but there’s no recognition of the true problem: a house is not a home.

Furthermore, if no one in that community owns the properties developed, or the income generated by that labor leaves, we have now made that community more vulnerable to gentrification. If someone else owns it, who will be enriched when the rent is raised or property sold?

It’s also often the case that, what we have to do to get something, we have to do to keep it. So we have to ask ourselves, do we plan to continuously incentivize outsiders to solve these problems? Are these outsiders committed to sustaining their solution? Are they going to be with that community when funding runs out?

What are the consequences you’re seeing when it comes to these narratives preventing investment in homegrown institutions?

Johan: On the human scale, we’re disconnecting people from their role in their story. As a result, they fail to see themselves as heroes. The implications of this are vast. When there’s a problem, not only is there a disinclination to solve it, there’s a disbelief that you can solve it. This disbelief is inherited by the next generation, and once you’re psychologically and socially disconnected from your own possibility, it seems as though you’re “the first” and that you are alone. You embrace your disinheritance and may even disregard the efforts of your peers because you intend to be ‘the one’. Each generation is starting over when they should be learning from their ancestors and each other. This prolongs the problem and reinforces what we see today: people not owning or feeling like they belong in their own communities.

Are you seeing any promising approaches to addressing under-resourcing of homegrown institutions?

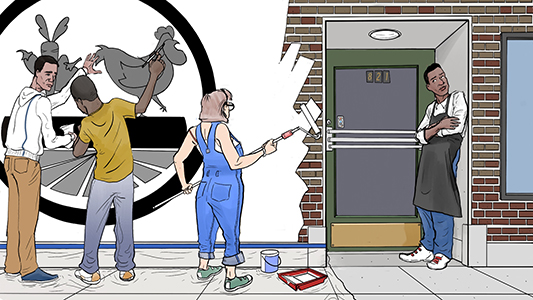

Johan: One promising approach I’ve committed to is co-design. When we create with, not for, an impacted community. The practice is catching on but is often done under the guise of engagement.

We can think of the pathway out of the imposed and into the homegrown as starting with outreach – this is practiced by institutions that exist in a community but are not connected to its community members. In order to deliver their service, they realize they need to actually talk to the community and tell them about what they have to offer. They might even hire locals to be the face of the program.

When they move past that point, they get to engagement, where they recognize the need to have an exchange. Not just telling but actively listening. This process should lead to actual changes in the service delivery. Sometimes engagement is considerate enough to compensate community members for their time and ideas. Engagement moves us in the right direction and may even result in the co-creation of innovative services but often falls short of facilitating lasting change in the institutions themselves.

Next we move to involvement. This stage allows the intended beneficiaries and impacted stakeholders to not only become an integral component of the service design and delivery, from inspiration and ideation to implementation and evaluation, it invites the community to be a part of leadership of the institution. Unfortunately, this can lead to tokenization. Especially, if you are the only one from your community who’s been invited to the table.

Ultimately, in this economic system, we need to graduate to a level of ownership, where the community members have a stake in the future of the enterprise, personally and collectively.

To get to this point, we need to start supporting people who are directly impacted by the problem to learn how to solve the problem, as opposed to paying outsiders who are not impacted by the problem to professionally not solve it.

Is there anything else you think people should think about when it comes to homegrown institutions?

Johan: Home is where you belong. It is where you’re safe enough to heal, grow, evolve, and become whoever you decide to be. Homegrown institutions facilitate that; they honor the essential capacities of the people in every community because they are made for them.

The underlying value of the homegrown institution is that they are regenerative. They regenerate latent talents and core capabilities that have been disabled in response to a hostile or enabling environment.

An imposed institution is like applying an artificial prosthetic in place of a missing organ. This can be helpful, even life saving, but homegrown institutions allow us to permanently move beyond the prosthetic. They facilitate lasting change and allow us, whoever we are, to truly feel at home in our community.

Johan Matthews is the Founder and Principal of Mutual Design, where he coaches and collaborates with local leaders and institutions to co-design and implement equitable change strategies. He also serves as the Community Engagement Facilitator at The Cooperative Fund of the Northeast, where he facilitates the development of equitable co-op ecosystems and provides culturally-informed technical assistance to ensure that communities excluded from economic investment can engage in cooperative enterprise.

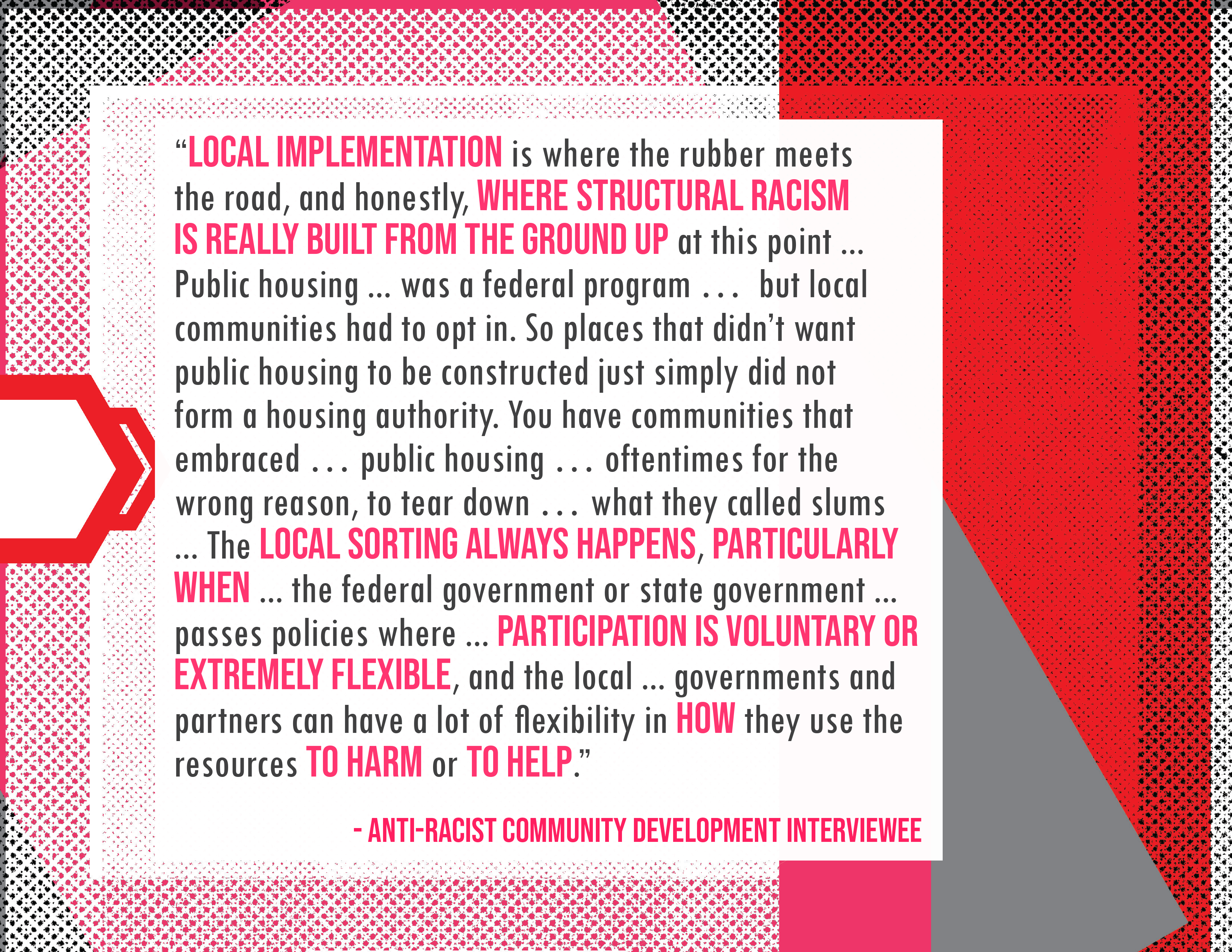

The interviewee is responding to the findings shared in the Anti-Racist Community Development Research Project, produced with support from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) to increase understanding of structural racism in community development and pathways to racially equitable outcomes that promote health equity. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of RWJF or ThirdSpace Action Lab.

© 2023 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation