Perspectives In Place: Our Grandparents’ Dreams, Our Grandchildren’s Birthrights

Written By Mordecai Cargill - 12 mins read

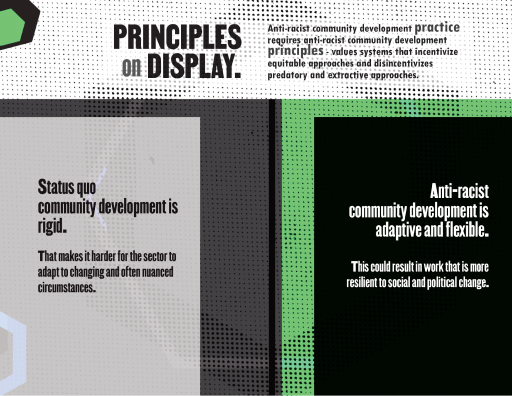

“You could get everything you needed between St. Clair and Superior, and at night it was lit up like Broadway,” says Peter Lee, one of our Glenville elders. Every majority Black urban area in the US has a neighborhood like Glenville, and chances are the same pattern of decline and disinvestment. Our anti-racist community development research found what many of us already know intuitively – that systems have “explicitly targeted investment to white households and white-majority communities, with corresponding generational and systematic underinvestment in communities of color.”

I’m Mordecai Cargill, a Glenville native and the co-founder and chief creative officer of ThirdSpace Action Lab. ThirdSpace Action Lab is a multidisciplinary research and strategy design firm that works with Clients and Collaborators to advance racial equity and create more liberated spaces for Black people. My inspiration comes from Glenville, an aspirational destination, a community where Black people sought and found glimpses of the good life.

In 2009, I left Glenville to attend Yale University majoring in African American Studies with a Concentration in Black Culture in the 20th Century. I relished in the legacy of Black Power activists and artists who built alternative institutions to meet the holistic needs of Black people and Black community – the kinds of visionaries who birthed the community development sector.

What I learned in school affirmed what I was seeing and gave me the language to describe what was happening – policymakers and urban planning practitioners made decisions that created these distinctly Black neighborhoods that are characterized by concentrated poverty, disinvestment, and blight. These are the conditions that our lauded Black artists were reacting to, they were organizing to change it. This convergence of creative and productive power led me to community development.

I came back to Cleveland in 2013, moved to Glenville in 2016. In 2018, my co-founder Evelyn Burnett and I launched ThirdSpace Action Lab. We understand that the status quo does not accurately address the nuances of Black life. We are passionate about nourishing places where Black artists, organizers, and community builders dedicate their talents to making the world a better place for Black people.

Across ThirdSpace’s literature review and interviews, we heard detailed perspectives on how community development history continues to reverberate in the field today. Pretty soon, I noticed a pattern — despite structural racism, Black people survived and built strong communities and institutions. Although I’m a Black history enthusiast, I know that focusing too intensely on the past can be a convenient balm, a signal of dissatisfaction with the present. Preoccupation with how things were can keep us from what is and more importantly, what we can strive toward. We must breathe life into memory to make it move, to push things forward. As our research named, “if we don’t acknowledge the history of structural racism and anti-racist work in the past, it’s going to be that much harder to build the future we’re aiming for.” This is very much the sankofa principle of looking back in order to go forward.

Interviewees in this research shared that truly anti-racist community development means rewarding “bolder, more creative approaches that are deeply rooted in community context and built from the priorities and solutions of the people that live in those communities, particularly residents of color and residents living with low incomes”. To realize our vision for the future of Black neighborhoods, we need to give space, time, and resources to residents and practitioners to imagine what community development could be … and that starts with candid, sector-wide dialogue about where things stand, where we want to get to, and what we need to close that gap.

I know that whatever happens next cannot overlook the impact of Black folks and our rich cultural, artistic, and organizing history. Our imagination has outpaced “the good old days”, our modern strengths will summon the great right now.

Mordecai Cargill is the Chief Creative Officer of ThirdSpace Action Lab and Co-Founder of ThirdSpace Reading Room. He previously served as the Director of Strategy, Research & Impact at Cleveland Neighborhood Progress (CNP), a community development funding intermediary committed to fostering inclusive neighborhoods of choice and opportunity throughout the city of Cleveland. Mordecai earned his BA in African American Studies from Yale University, with a concentration in Black Culture in the 20th Century.

The author is responding to the findings shared in the anti-racist community development Research Project, produced with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) to increase understanding of structural racism in community development and pathways to racially equitable outcomes that promote health equity. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of RWJF or ThirdSpace Action Lab.

© 2023 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation