Reintroducing Rural America: Places of Possibilities

IN(TER)VIEW, Stephanie Johnson - 7 min read

We chatted with Stephanie Johnson about (mis)conceptions about rural America, cross-cultural coalition building, and philanthropic approaches to supporting organizing in rural communities.

Could you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got into your work?

Stephanie: From a young age, I was curious about racial identity. My father is white and American, and my mom is African, Indian, and French Creole and from the Seychelles Islands. I grew up with this multiracial family in a rural community and saw how my mom was treated differently than me and my dad. In college, I wanted to explore racial dynamics further so I led an organization called the Race Dialogue Project, where we tried to push the conversation forward on topics like race, ethnicity, language, identity, and culture. When I got into philanthropy, I wanted to continue this kind of work. At the Kresge Foundation, one of my roles was working with a senior team of leaders on our DEI process, embedding racial equity into our strategies, and learning. Now at Rural Democracy Initiative (RDI), I help to lead our racial justice planning process and how that shows up in all of our work from grantmaking to capacity building, to our grants management, internal operations, and hiring process.

The other thread was working in startups and social enterprises, before transitioning to philanthropy. This idea of businesses advancing social, cultural, and environmental issues attracted me, but I quickly found out that organizations still have to make a profit and make hard choices. The social good side of business gets deprioritized for profit. I wanted to find something where I went to bed and woke up thinking only about how to make social change. t. That’s how I found philanthropy. It has challenges, but I’m grateful I found a place that reflects where I grew up, and is lifting up people fighting to change things in small towns and rural communities across the country.

At RDI, you invest in organizing in rural communities. What is your approach and strategy?

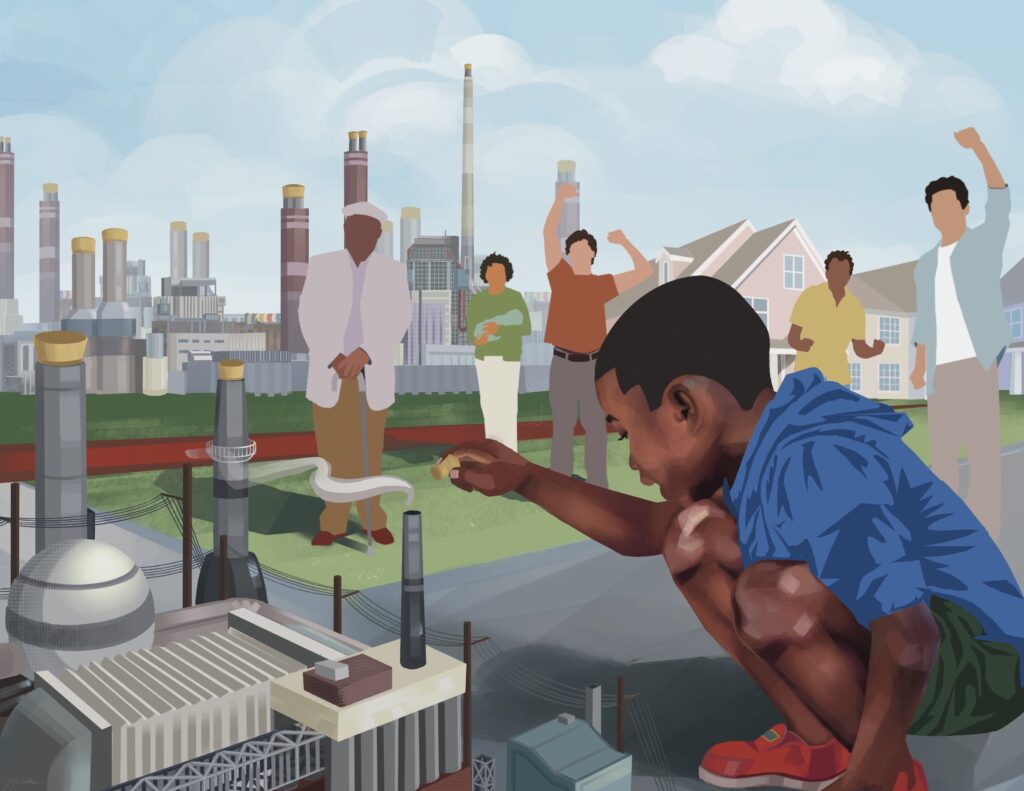

Stephanie: Rural communities have been disinvested in for decades by philanthropy, private industries, business, and government, and this has led to system degradation, from transit and rural hospital closures, to stagnant wages and lack of job opportunities. The only way for communities to change the conditions in which they live is to organize. To bring together folks from different backgrounds and figure out what they most want to work on.

As funders, we’re not determinative. We give general operating support, and we let grantees figure out what’s most important to their communities to organize around – keeping an elder care center open or improvements in manufactured housing. Right now, our network is excited about the possibilities from the Inflation Reduction Act – whether that’s for solar on businesses or houses, electrifying school buses, or whole home repairs.

There’s a million things people want to work on, but we should let those communities decide. Organizing in tandem with civic engagement can create that big change that we want to see in the world. It’s working on the issues you care about, and it’s using what we all have – our power to vote.

Can you share some trends you’re seeing in terms of rural democracy across the country?

Stephanie: On the positive side, we’ve seen an explosion of organizations working in rural communities in the civic engagement ecosystem. Many are homegrown, a couple of people that really care about where they live. Statewide organizations have started to add rural chapters and organizers to their work, realizing that you can’t truly have statewide power without including rural communities.

On the other side, we’re also facing the rise in authoritarianism and white supremacy, though it’s not new. Rural communities take the brunt of those trends. We’ve had grantees host events and the Proud Boys or militia show up with guns to their events. Some BIPOC leaders, especially around elections, have to relocate given threats to their safety. We support our groups to weather those storms through capacity building, security training, or rapid response contributions with no grant report or application. We let people decide what will make them feel safe. We also support through healing justice. We partner with Wild Seed, a network of mental health and spiritual practitioners helping people deal with aftereffects of a crisis.

Another trend – one in four people in rural America are people of color, an increase from the last census. In some rural communities, BIPOC folks are the majority, like in southwest Georgia, South Texas, rural Alaska.

We’ve seen more multiracial coalition building. One of our grantees, Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), works with white, rural communities to shift their understanding, and show up in the movement in solidarity with Black and Latin/a coalitions in Georgia, North Carolina, Ohio, and Kentucky to deliver change. When white rural communities show up to these multiracial coalitions, it’s important to ask, what role should we be playing? To listen and see where they can add value. When you break down the differences, folks want the same things. A coalition in Michigan developed a People Power Agenda to identify priorities, and folks wanted a better cost of living, increased wages, and clean water. Anti-racist work includes moving white rural communities in solidarity with communities of color, to further support multiracial coalition building. I’m hoping this trend will continue in rural America. I’m excited for it.

You started to touch on some of the misconceptions and false narratives about rural America. What are others? What is an alternative narrative that you’d like to put forward?

Stephanie: It is not true that rural America is only white folks. Another stereotype is around perceived progressiveness. We found that the majority of rural communities support abortion access and broad economic policies, increased minimum wage, better health care. They’re anti-monopoly. They want corporations to pay their fair share of taxes.

Rural is not a monolith, not with race or age. Rural young people are the most potentially progressive folks on issues around climate, abortion access, gun violence. They want changes. But research shows they’re actually the least contacted of any group. Rural young people are this huge missed opportunity; they’re the most swingable and persuadable.

But rural people in general are very swingable. Across midterm and presidential elections, we’ve seen rural people swing quite a bit. Twenty years ago, a lot of rural people in unions voted very blue. There’s misinformation about who rural people are, what they care about, who they vote for, and how they think, but again, they’re not a monolith.

There is a rural culture. Community development uses a lot of acronyms and talks in “a very highfalutin way,” as my dad would say. You just need to talk to people and ask what they care about. Spend time with people, digging deeper, asking questions, being open to listening, and sharing your own story. This deep canvassing can really build a base of people to take on bigger challenges together. Rural folks have outsized political power. To make a difference in any state legislature, you need rural folks to be a part of your coalition.

Are there any closing thoughts you have for anti-racist community development practitioners?

Stephanie: Figure out how community development can work in partnership with civic engagement organizations. We have great organizations focused on community development, or on civic and voter engagement. There are some groups bridging the two; with issue organizing, doing projects in their communities, and engaging voters. But we don’t have those amazing groups in every community. I’d challenge community development practitioners to know who else is organizing in their community for the long term. Figure out which organizations and individuals hold your same values. Civic engagement organizations do power mapping really well and know how to make change in their communities. Be in partnership and in coalition with these groups. What could you all accomplish together?

Stephanie Johnson is the Program Officer at the Rural Democracy Initiative – which includes the Heartland Fund (501c3) and Rural Victory Fund (501c4). RDI is a funder collaborative building civic and political power in rural communities across the U.S. Previously, Stephanie worked at NEO Philanthropy, a national funder intermediary and the Kresge Foundation, a national foundation based in Detroit. Stephanie grew up on a farm outside of the small town of Denton, Maryland and is passionate about making change for rural communities.

We sat down with

We sat down with